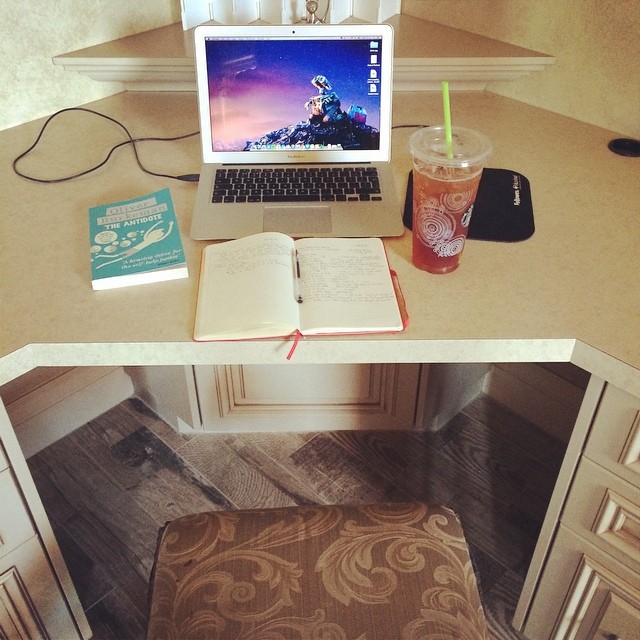

As previously mentioned, this week I’m a guinea pig for Canongate’s Nudge Your World project. I’m reading The Antidote by Oliver Burkeman – billed as “happiness for people who can’t stand positive thinking” – and trying to live by its learnings.

If you missed it, catch up with Part I.

Chapter 3: The Storm Before the Calm

In this chapter, we take on the Western fascination with Buddhist Zen, calm, and meditation.

I’ve been tasked with living the learnings of this book, but I’d be hard pressed to beat Burkeman’s own test of these theories. As he shares in the book, he took a five-day meditation retreat. Unfortunately the only part that rubbed off on me was his annoyance at having Barbie Girl by Aqua stuck in his head for the first day and a half. YOU’RE WELCOME.

What I did learn is that meditation takes more than a few minutes to achieve. The pursuit of enlightenment is huge; but so is the pursuit of 5 minutes’ silence.

I practice yoga, casually, mostly for exercise. It’s the perfect antidote to sitting hunched up in an office chair and typing all day long. Without getting all woo-woo on you, it’s true that meditation goes hand-in-hand with yoga practice. There is great value in focusing your mind, removing distraction, and letting thoughts float by without judgement.

I’m mindful of not spending too much time on the computer, and of limiting the number of times I hit refresh on my inbox. But sometimes casting it aside and getting my feet on the mat still seems hard. This week I focused on casting that resistance (read: laziness) aside and getting in at least 10 minutes of ashtanga each day.

I’m not about to run off on retreat, but I’ll tell you what: it’s better than The Little Book of Calm.

Chapter 4: Goal Crazy

Burkeman’s next chapter opens with some alternate theories on the reasons for the Everest disaster in 1996. In short, that year more climbers died than in any other year in the mountain’s history. Most of the reasons given have been unsatisfying, but one or two can go a long way to explain a problem in our culture.

Burkeman’s theory? Goal-setting is to blame. He notes that it is our fear of uncertainty that’s killing us. When we’re uncertain, we crave the security of certainty, which leads us to double down on our plans. We see our goals as a road map to our future. If only we can live out those plans, we think, we can live without uncertainty.

The idea of embracing uncertainty is an interesting one – and one I feel I’ve lived out. During my final year of university, my friends and flatmates were caught up in applying for every graduate scheme going; applying for jobs they were and were not qualified for. A pragmatic move to make for the class of post-recession 2009, to be sure. But after spending ages 5-22 in full-time education I was ready to embrace uncertainty and go out into the world and see where the wind took me.

The part that I bristled at was the idea of eschewing goals altogether. Most of the goals and single-minded goal-setting junkies that Burkeman makes examples of suffer from a lack of moderation. As he points out, there’s a lot of misinformation about the virtue of goal-setting out there. On top of that, most of the workplace goal-oriented activities that are prevalent in corporate cultures are also largely useless, putting strain on workers rather than motivating them to work harder and/or smarter.

In the face of these examples, goal-setting seems like a great way to succeed in one venture and likely fail at all others. Too-broad goals are difficult to juggle, and precise ones can take over your life.

Either way, I can definitely chalk my resistance up to the notion of giving up goals. I’ve always been very goal-oriented. Get X grades to get into university. Get on the study abroad programme. Win that award. Get this or that published. Blog every day in August.

The thing is, my goals have always been fairly finite, and have seldom fallen into the trap that Burkeman outlines: withholding happiness until they are achieved.

For me, the dangerous goals are the ones that are applied to arbitrary numbers, like getting 20,000 Twitter followers, or making £50,000 per year; or which – as the author notes – withhold happiness, keeping us from enjoying the journey. I’ll happily lay off those ones.

But I’ll tell you what: I’ll give up on that goal of avoiding uncertainty.