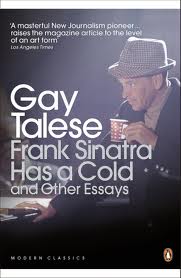

These past few weekends I’ve mostly been reading longform journalism. Last week, it was Frank Sinatra Has a Cold and Other Essays by Gay Talese.

The title essay is one of the most cited profiles – and most successful write-arounds – of the contemporary era of journalism. For longform journalists, it’s the gold standard.

Lately I’ve been listening a lot to the Longform podcast, on which Gay Talese was a recent guest. On one hand, hearing about his early life and the formative experiences that made him a writer were fascinating. For example, he attributes much of his ability to get the most out of his interviewees to his mother and her tailoring business, where he used to hang out and later work as a child and a young adult.

The more I listened to him, though, the more I became aware of how practiced he has become at telling his own story. We all do. The extent to which we self-edit, exaggerate our current-day perspective and project it onto our young, growing, unwitting selves is so ubiquitous that we seem to absorb it without question. “That was the moment when I realised that I wanted to be a ___” is, to my mind, one of the most reverse-engineered and overused sentiments of our time. It’s one of the key tools in any interviewee’s toolbox. Frankly, it’s bullshit.

Yet it’s a story we’ll lap up over and over again. It’s a story that journalists spend their lives trying to get at in their various interviewees. Perhaps some don’t spell it out, but it’s often the hook that makes a story fizz. In fact, one of the best moments in an interview is when the interviewer points out an overarching theme that the interviewee has not been aware of in his or her own work.

So Gay Talese is on this podcast, and the interviewer points out that Talese’s subjects have been primarily men, mostly Italian-Americans of a certain era, and frequently middle-aged. If, like me, you’re a young woman growing up in the Millenial era, these are ripe not with the wisdom of an age, but history’s sexist 60s stint in which the only women who feature – beyond those hanging off his arms at casinos – are his beloved mother, daughter, or divorcée. And yet…

Talese’s work is as good as everyone says it is. ‘Frank Sinatra Has a Cold’ dwells not on the bad-boy manner, the nervous entourage, or the volcanic emotional turns (though all of those things are present and correct). It’s a cinematic journey, taking in the man and turning him into an empathetic figure cute adrift in fame and without the comfort of a home. A man of the road with a near-estranged beloved daughter and a lot to live up to at the landmark of his fiftieth birthday. It’s such a well written and curated journey with all the drama and ridiculousness of a great melodrama of its time. It shows vulnerability and the self-righteousness that follows in the event of good luck and a big relief. It shows a man unmoored without making him weak or in some way beaten.

It’s so good that I almost forgot I was reading some old man writing about some other old man. Which is more than I can say for most of the stuff I read at school. I came a skeptic and left a devotee.

This blog post was inspired by Natasha Vargas-Cooper’s piece on Why We Should Stop Teaching Novels to High School Students, and as a reminder to myself that there are cultural pieces out there that are by men, about men, and mostly for men, to which I can still relate – as long as the writing is good.

A choice quote:

With most women Sinatra dates, his friends say, he never knows whether they want him for what he can do for them now – or will do for them later. With Ava Gardner, it was different. He could do nothing for her later. She was on top. If Sinatra learned anything from his experience with her, he possibly learned that when a proud man is down, a woman cannot help, particularly a woman on top.