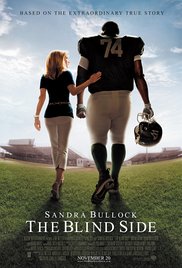

Watching and reviewing a film after it has received so much acclaim and a contested Oscar win (alongside a Raspberry Award for All About Steve) is a tough business.

The Blind Side has been lauded as being an American movie with all the sickly sweetness of a Hallmark card, but that analysis doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface of this film. A number of delicate balances are held in place throughout this emotionally-charged and culturally complex film; a fact that doesn’t seem to have gained much attention.

Based on a true story, The Blind Side is the story of Michael, or “Big Mike” – a burly, close-mouthed African-American. The 18 year-old child of 12 has a dark past and troubled history, but no-one wants to get close enough to find out what’s going on behind his gentle-giant demeanour. Admitted into a private Christian school alongside a friend, the faculty take a chance on him but their belief in him, it seems, is limited. Enter Leeane, your atypical Southern belle with a strong disposition and a knack for getting her own way, and you have a matriarch on a mission.

Accepted into her home, and eventually her family, Michael soon becomes a successful student and sought-after American football player. Though it follows the model of a life-changing tale of overcoming adversity on the path to success, there is something of a silent voice of reason keeping its believability in check.

Bullock’s performance is rightfully awarded, playing Leeane with a nuance and precision that is rarely seen in films that feature dichotomies of race. For much of the film Michael is more interesting, but it is Leeane’s strength of will and the delicate vulnerability beneath her disposition that you walk away remembering most.

Though overlong, the film hits its points of tension with precision and grace, complementing the characters’ relationships and struggles. The film really tests your belief in Leeane, but you’re forced to stick by her whether you want to or not. Thought he film is never explicitly told through his eyes, we walk alongside Michael every step of the way.

The issues of race and religion are not contrasted beyond their natural importance, sparing us that saccharine Hallmark experience the synopsis of this film implies. These themes are comfortably present but not overt and never given undue importance within the narrative.

Although this is not a new story, the subtle grace with which it is told and the myriad of fantastic performances of all of the family members makes it a surprising and memorable film.

The Case of 3D Filmmaking

This week, I finally bit the bullet and went to see Avatar in 3D. Better late than never, right? My friend and I have never been fans of the booming trend of 3D filmmaking, but we were never certain why. Needless to say, we soon ascribed to the Kermode school of thought. You’ve heard the arguments, so let’s not drag this out.

Eye-strain: The 3D technology is not yet perfect, as well we know. Our eyes are all different, the glasses don’t necessarily fit well, and the images on screen can be flawed. At several points during Avatar I noticed that the 3D imaging was out of focus, see-through where it shouldn’t be, or plain unpleasant to look at. So much for that Oscar for Best Cinematography.

30% colour loss: This is Kermode’s pet argument, and let’s be honest, it’s a good one. Let’s say that Avatar and Alice in Wonderland are the two biggest 3D films so far. Yes, one is the pioneer in 3D filmmaking and the other is retrofitted, but bear with me. Avatar purports to be colourful, replete as it is with lush meadows, vibrant creatures and kaleidoscopic images. Think how colourful it could have been if we weren’t all seated in the dark wearing a pair of sunglasses. Alice in Wonderland, in contrast, is a dark film with signature Burton shadows. Perhaps I’m heading down the wrong path here – after all, fans of Burton’s Gothic auteurism might have a predilection for donning massive frames and relish doing so in the dark.

Disjointed planes of vision that force your eye onto particular parts of the screen: This is the culprit that causes eye-strain. All that has to be said is this: peering through 3D specs is a very limiting way to watch a film. Your eyes are naturally drawn to the lightest part of the screen; we view a film by scanning the images and resting our eyes where it feels most natural. This organic quality is lost in the 3D world.

The final – the behemoth – argument behind the 3D revolution is anti-piracy. So far, most (if not all) of the big 3D ventures have been screened in 2D alongside the main feature. Surely this is not anti-piracy so much as monetisation and creating hype to herd in the willing? Some cinemas still don’t have 3D technology. Others have enough auditoriums to screen both versions and conceivably still make money from those who missed out on a sold-out 3D screening. How long will it be until we’re left with 3D or nothing? Hopefully it will be a long while. Ideally, it will be never.

So. Having held out for so long, I put my preconceptions aside and watched Avatar – The Film To Change The Industry. I sincerely hope it’s the last time I will have to watch a 3D movie. Moreso, I hope it’s the last time I have to sit through a 3D trailer. Yowza!

What are your thoughts on the 3D revolution? An innovation in filmmaking or a gimmick with a hype machine behind it?

[Image from UNSW website.]

Interview with Mark Millar at Glasgow Film Festival

Kick Ass will premier with an advanced screening at the Glasgow Magners Comedy Festival on Wednesday 24th March. The UK-wide release date is for the much-anticipated film is Friday, 2nd April.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- …

- 65

- Next Page »