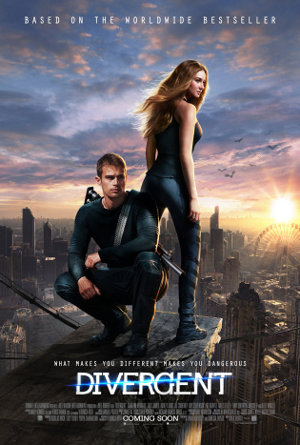

Divergent came out in cinemas recently and one of the article headlines I happened across about it was this: ‘Is Divergent Just a Poor Man’s The Hunger Games?’

It is not a bold statement to say that our contemporary mainstream culture is risk-averse. There’s a reason why the makers of Pirates of the Caribbean managed to tack 3 impostor sequels onto the original movie (which itself was based on a funfair ride, of all things), and why it was then virtually remade again in the old west in the form of The Lone Ranger – and why all 5 of those films starred Johnny Depp.

Hollywood looks out for what’s popular, and packages it up in movie form then dangles it over us to see if we bite. But its formula still stinks.

The success of the Harry Potter films and Twilight saga are the monoliths of the YA genre to which Divergent belongs. Then there was The Hunger Games. But between them lies a graveyard of flops. Remember City of Bones, The Host, The Golden Compass? Not really, except that they went nowhere. While Hollywood correctly identified that hugely popular books can be parlayed into hugely popular blockbusting films, something vital about these niches remains misunderstood.

Another thing that gets lost in translation from publishing phenomenon to big screen is the ability to get the non-native audience on board. The Harry Potter franchise had an entire generation, and its parents, behind it. The Hunger Games was able to bank on the gladiatorial nature of the series, and later some of its major themes and social commentary. But one of the resounding calls from the non-native Divergent audience – even from those who have already seen it – has been, “but what is it even about?!”

This got me thinking about our limited capacity, as a culture, for understanding niche trends and the popularity of some cultural items. It’s not just audiences, either; it’s also cultural critics.

Recently I took part in a panel on film criticism. It was one of the old guard tricks of inviting internet people along to defend their right to critique, but one of the major issues I picked up on with a colleague, Eddie Harrison, was that the current model of broadsheet criticism wherein (and I genralise, but not much) older white guys do their Roger Ebert thumbs-up thumbs-down bit is ridiculously, hilariously outdated. I work alongside and respect many of these guys dearly, but as a group our attempts to look into and understand these cultural artefacts and to examine what made them popular within their niches stinks.

I don’t want or mean to be uncharitable to great writers and critics here, but as an example, NPR Pop Culture Happy Hour was one such podcast in which its group of critics watched and discussed Divergent. Only one of the four participant critics had read the book, and appeared to have a deeper understanding of the book’s themes and the meaning behind the factions and other quirks of the storyworld. None of them really commented on the Divergent fandom. This is by no means an isolated example – it happens all the time, and is often my reason for pitching reviews of films like The Hunger Games and, soon, The Fault in Our Stars.

While it’s valuable for a critic to come to a work fresh and take the place of the potential uninitiated audience member, I frequently can’t help but feel like there are too many critics in broadcast studios and on web pages who fail to understand what the work is about, where it is coming from, and what made it so popular within its niche. People who haven’t looked into the source material or read native fans’ critiques. Understanding the intended audience can be hugely enlightening and key to really ‘getting it’ – even to getting the Hollywood studio’s drive to make a piece of art or cultural work for a bigger audience. Whether the film itself succeeds or fails on its own is also important, but doesn’t give a very full picture, does it?

So why is it that we’re so bad at trying to understand the seed of these films’ popularity? What does it really mean when a niche popular adaptation fails in the mainstream? Is it always a bad adaptation, a poor piece of work that doesn’t stand on its own, or would a greater appreciation of the source material make us more open to it? Who are the arbiters of taste in these cases, really? The studios? The critics? The original audience?

Are movie adaptations just a poor man’s book, or are we a poor man’s audience?